Document Type : Research Paper

Authors

- Seyed Vahid Nabavi-Zadeh Namazi 1

- Mohammad Bagher Ghahramani 2

- Zeinab Ghasemitari 3

- Mohammad Javad Zarif Khonsari 4

- Amirsaeid Moloodi 5

1 PhD Candidate of North American Studies, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2 Associate Professor of Performing Arts, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

3 Associate Professor of American Studies, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

4 Associate Professor of World Studies, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

5 Assistant Professor of Foreign Languages and Linguistics, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran

Abstract

The 1979 Islamic Revolution marked a pivotal moment in the political relations between the U.S. and Iran, resulting in a “soft war” that primarily unfolded in the media, particularly within films. This study aims to analyze how the selected film, Septembers of Shiraz (2015), represents post-revolutionary Iran from a cognitive perspective. The Islamic Revolution is characterized by distinct signifiers, including anti-Zionism, the duality of the oppressed and the oppressors, legality, Islamism, republicanism, and the rejection of the United States. Rival discourses attempt to dislocate each of these signifiers to delegitimize the hegemon discourse of the Islamic Revolution. This analysis employs a combination of three theoretical frameworks and cognitive construal tools at the micro-level: Talmy’s (2000) force-dynamic paradigms, the multimodal conceptual metaphor proposed by Forceville (2006, 2008, 2016), and the metonymy-producing relationships suggested by Radden and Kövecses (1999). A macro-level analysis will utilize Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory to uncover the hegemon discourse’s semiotic system using the micro-level data. The results demonstrate that this film employs the repetitive metaphor of IRAN IS PRISON, the metonymy of MEMBERS FOR A CATEGORY, and the force-dynamic paradigm of the revolutionaries as a strong Antagonist/ the Jewish society as a weak Agonist. Discursively, the Iranian revolutionaries are portrayed as irrational, dogmatic, and narrow-minded individuals who are drawing their other-making border with all those who are not devoted to the Islamic revolution. Rejecting anti-Semitism, the revolutionaries’ irrationality, Jewish sacred suffering, and messianic redemption are some of the signifiers articulated by this film.

Keywords

- Cognitive-Critical Discourse Analysis

- Hollywood

- Islamic Revolution of Iran

- U.S

- Multimodality

- Septembers of Shiraz

Main Subjects

![]()

This is an open access work published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0), which allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use (https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-sa/4.0/)

- Introduction

The disparity between reality and media portrayals has prompted numerous attempts to describe and explain how and why media representations are conceptualized from the external world. These efforts have established media representation as a fundamental concept in contemporary cultural and media studies. Among the various media products, U.S. cinema, following its political perspectives on post-revolutionary Iran, holds an important position in providing representations of Iranians.

Following the hegemony of the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the establishment of a new socio-political structure, the definitions of in-groups and out-groups have evolved. Individuals once regarded as part of the in-group have been excluded from the revolution’s inner circle. The discourse surrounding the Islamic Revolution comprises several key components. According to Cottam (1979, p. 9) “Primarily, it encompasses a widespread nationalist feeling that plays a crucial role in the Iranian Revolution”. The initial borders with out-groups are drawn between Iran, the Soviet Union, and the West, particularly the U.S. National populism serves as another signifier that emphasizes anti-imperialism and national independence. Amid Zanjani (1998, pp. 121-142) summarizes the significant aspects of the Islamic Revolution as follows: “Adherence to Islam and the Quran, defending the oppressed and downtrodden, avoiding alignment with Eastern and Western powers, achieving social justice, Islamic education, and upbringing, and rejecting the dominance and tyrannical rule of oppressive powers”.

On the other hand, the West, particularly the United States, which post-revolutionary Iran has rejected, has rearticulated its discourses regarding this country and turned to its big others. Therefore, these discourses have exerted various forces to alter post-revolutionary Iran’s intrinsic tendencies. One of the most significant tools for exerting this force is cinema. As a result, numerous films and documentaries, especially within American cinema, have portrayed Iran and its people in a negative light. However, there is a notable lack of academic studies that apply cognitive semiotics to American films, utilizing media-based discourse analysis to identify these portrayals. The present study aims to describe the way in which the images of Iranians are cognitively conceptualized by analyzing the multifaceted metaphors and force-dynamic paradigms at a higher level, employing Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory. Accordingly, it seeks to provide a brief overview of the general approach of American films toward Iran and its people, while exploring this approach through cognitive conceptualizations. Septembers of Shiraz[2] is the first to focus on the Jewish society in post-revolutionary Iran, making it an appropriate case study. This selection is informed by the revolution’s antagonism toward Zionism, as well as the involvement of the U.S. in supporting the Zionist movement in opposition to post-revolutionary Iran.

The film has a rating of 6.2 out of 10 on IMDb. According to the Rottentomatoes website (2024, Sep. 11), it has a 47% audience score and a mere 31% score from critics. With the victory of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the United States and Zionists encountered a discourse that featured many nodal points, including “opposition with Zionism”. September of Shiraz, as a product of Hollywood and the U.S., seeks to dislocate the signifiers associated with the discourse of the Islamic Revolution and, in doing so, to confront and oppose it. Like many other Hollywood productions, this film engages in a cognitive struggle to sway its audience against this discourse. The central research problem of this article focuses on how this film is other-making with the Islamic Revolution discourse and what cognitive tools are employed to dislocate it. As a result, this study explores two key questions: What cognitive tools are employed to represent discursive encounters in September of Shiraz? And what image of post-revolutionary Iran does this film convey to its audience? To answer these questions, this study elaborates on Talmy’s (2000) force-dynamic paradigms, Radden and Kövecses’ (1999) metonymy-producing relationships, and Forceville’s multimodal theory of metaphor (2006, 2008, 2016).

This three-level study starts with cognitive analysis at the micro-level, followed by context-based analysis at the meso-level, and concludes with socio-political analysis at the macro-level. This combinatorial approach delineates the drawn borders between in-groups and out-groups and examines the semiotic system articulated by the selected film concerning the socio-political context of post-revolutionary Iran.

- Literature Review

Scholarly articles, including those by Alcantara and Michalack (2023), Atmaja (2021) and Sutandio (2020) have focused on the application of semiotics within a singular case study. A significant number of investigations examined collections of interconnected films or the complete works of specific directors. Additionally, many studies have explored cinematic and technical aspects such as editing, production design, and mise-en-scène, or have explored particular themes or ideologies. Nevertheless, all these works have effectively employed non-cognitive semiotic analysis. Still, they have made the best use of non-cognitive semiotic analysis; Murod (2021) is one of these studies. Sunendar and Rasyid (2018) showed a critical discourse analysis at a meso-level of the film Rudy Habibie (2016) using Fairclough’s theoretical framework (1995).

Amirian et al. (2012) conducted a critical analysis of the film Iranium (2011) which is recognized as an anti-Iranian documentary. Many researchers who previously focused on metaphor in actual discourse would agree that a primary function of the metaphors encountered in discourse is to provide coherence and consistency (e.g. Cameron, 2003; Deignan, 1995; Musolff, 2006). Moloodi and Nabavizadeh Namazi (1400 [2021 A.D.]) have examined the metaphorical and metonymical conceptualizations in the film Snow on the Pines (2012) based on conceptual metaphor and metonymy theory. Using a descriptive-analytical methodology, Mozaffari et al. (1400 [2021 A.D.]) analyzed the language and image of The Salesman (2016) based on the conceptual metaphor theory of Lakoff and Johnson (1980 ) and the multimodal metaphor theory of Forceville (2006, 2008).

A limited number of analyses have been conducted regarding the studies on Septembers of Shiraz. Coletsou (2023) explored the representation of Iran in American popular culture through audiovisual media. One of the instances examined in this research was Septembers of Shiraz. Coletsou’s findings revealed that most audiovisual depictions of Iran portray it as Oriental, underdeveloped, and complicit in human rights abuses. Farahat (2023) investigated whether producing fair and unbiased films and television shows that depict the U.S.–Iran conflict, could have a more positive impact on Hollywood studios and their global audiences, compared to the current one-sided and stereotypical portrayals.

Similar films can be cited that explore themes such as cultural identity, the Iranian Revolution, and immigration. Although these films approach their subjects differently, they highlight various social and political changes and their impacts on people’s lives. Not Without My Daughter (1991) tells the story of an American woman attempting to escape from Iran with her daughter while navigating a closed, patriarchal society. Research analyses of the film primarily focus on its portrayal of Iran as a "constructed other" in contrast to the West (Dahbia & Cylia, 2022). Argo centers the operation to rescue six American diplomats during the Iran hostage crisis. Similar to Septembers of Shiraz, this film portrays the atmosphere following the Iranian Revolution, but from a political and espionage perspective. Some works conducted on Argo (Wahyudi, 2024; Wu, 2022; Selim, 2016) have demonstrated that through its historical narratives, the film emphasizes contrasts between Iran and the U.S. and reinforces anti-Iranian discourse. Women Without Men (2009) narrates several Iranian women during the coup of August 28. This film, like Septembers of Shiraz explores the effects of historical events on individual and social identity (Ceuterick, 2020).

Research related to these films indicates that themes associated with Iran following the Islamic Revolution are frequently accompanied by stereotypical representations, cultural conflicts, and political confrontations. Septembers of Shiraz also fits within this framework, focusing on discrimination against minorities and migration. The studies mentioned above indicate a significant gap in research that integrates the cognitive construal tools of metaphor, metonymy, and force dynamic for multimodal discourse analysis of films. Previous works have typically employed only one tool—either metaphor or metonymy—and have been analyzed through either discourse analysis or multimodal analysis. Moreover, those studies utilizing discourse analysis and semiotic analysis did not incorporate Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory, the only study combining cognitive linguistics with this theory is Shokati Moqarab (1399 [2020 A.D.]) and Shokati Moqarab et al. (1400 [2021 A.D.]). However, the following study can be regarded as one of the first to conduct cognitive multimodal discourse analysis by employing three construal tools (metaphor, metonymy, and force dynamic) and analyzing them through the lens of discourse theory.

- Theoretical Framework

This section examines the theoretical and methodological foundations of the research concepts and components. The current study is grounded in various approaches and theories. To establish a comprehensive framework for discourse analysis, this section first reviews the existing approaches in discourse analysis, including Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory, and subsequently introduces cognitive interpretive tools.

- 1. Discourse Analysis

Laclau and Mouffe (2001) argue that discourse is a constructed integrity that emerges from the act of articulation. Discourse can be defined as a system of meaningful actions that shape the identities of subjects and objects (Howarth & Stavrakakism, 2000). Jorgensen and Phillips (2002, p. 38) state that:

The starting point of the theory is that all articulation, and thus everything social, is contingent possible but not necessary. This is both the philosophical foundation of the theory and its analytical motor. It is only by constantly looking at those possibilities that are excluded that one can pinpoint the social consequences of particular discursive constructions of the social.

Sign systems consist of signifiers that acquire relatively fixed meanings by associating them with specific signified concepts. This fixed meaning can be illustrated through selected examples that effectively convey that meaning. Discourse conflicts utilize the production and reproduction of signifiers to establish hegemony; these conflicts are centered on a focal signifier. Laclau and Mouffe (2001, p. 105) define articulation as any action that creates a relationship between elements, thereby explaining their identity as a consequence of this articulation process.

- 3. 1. Identity (Self and Other)

According to Laclau (1990), identity is an act of power; thus, identity itself is power. Norval (1996) views identity formation as a political process primarily influenced by power. Any attempt to impose a specific identity or to shape social identities is characterized as a power-building action that inherently resists such imposition.

- 1. 2. Chain of Equivalence and Logic of Difference

The logic of equivalence represents a form of political simplification that increases the variability of elements, while reducing the number of available subjective situations (Andersen, 2003). This logic articulates several discursive elements or signifiers, including identities and subjective situations. The dimension of difference illustrates the composite or continuous nature of communication, which not only legitimizes identity differences among elements, but also supports the existence of distinct, separate, and autonomous entities (Glynos & Howarth, 2007). Shokati Moqarab (1399 [2020 A.D.]) finds this chain and logic through combining discourse theory with force-dynamic patterns.

- 2. Cognitive Conceptualizations

Discourse analysis is an approach that operates at the macro-level, necessitating tools to describe it at the micro-level. These tools are developed through cognitive linguistics, offering a variety of construal tools, each providing a distinct interpretation of a text. This section will introduce several construal tools that will be analyzed in the following study.

- 2 .1. Metaphor

As Kövecses (2010, p. 4) states, a “metaphor is defined as understanding one conceptual domain in terms of another conceptual domain…conceptual domain A is conceptual domain B, which delineates a conceptual metaphor”. In other words, Kövecses (2010, p. 4) explains, “A conceptual metaphor consists of two conceptual domains, in which one domain is understood in terms of another”. Metaphorical expressions are derived from a conceptual domain to facilitate understanding of another conceptual domain. The former is referred to as the source domain (e.g., WAR, FOOD, JOURNEYS, PLANTS, BUILDINGS), while the latter, which is comprehended through this process, is known as the target domain (e.g., IDEAS, LOVE, SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS, ARGUMENTS, LIFE, THEORY). Conceptual metaphors utilize abstract concepts as targets and physical concepts as sources. By employing the source domain, we can gain insights into the target domain (Kövecses, 2010).

One of the key points made by Forceville (2002) is that in cognitive studies of metaphor and linguistics, it is widely accepted that a source and target domain can be identified, with mappings occurring from the source domain to the target, rather than the reverse. Consequently, the source and target cannot be interchanged. To be precise, metaphors are, in a technical sense, asymmetrical, and the mapping of elements is unidirectional. In addition to language, conceptual metaphors can be conveyed through various media, with visual media—particularly cinema—being among the most significant and tangible forms (Forceville, 2015).

- 2. 1. 1. The Filmic Metaphor Identification Procedure (FILMIP)

Cognitive linguistics has a conceptual essence and foundation, making its representations both verbal and non-verbal. The method utilized for extracting, identifying, and analyzing metaphors is FILMIP, conceptualized by Mir (2019). FILMIP consists of seven systematic steps divided into two main phases.

Phase 1: Step One: Understanding the Overall Picture; this step (content analysis) consists of a series of sub-steps that a researcher must undertake to arrive at the overall meaning and main idea of the selected film. This step is divided into two parts: micro and macro analysis. In the content analysis phase, the analyst identifies and describes all the communicative elements occurring within the narrative of the film, thereby recognizing and describing both the referential meaning and the more symbolic meaning of the film.

The first step contains several preliminary actions, which include the following:

- Content Evaluation: (Watching each film version at least five times.)

- Identifying Analytical Units (dividing and categorizing the film into shots, scenes, and sequences.)

- Identifying and Describing Modes. Communication modes are identified and described based on genre: Written (e.g. typographical features), Spoken (monologue/ dialogue; voices-off; voices-over; tone-of-voice), Music (diegetic/ non-diegetic; composed; appropriated), Non-verbal sounds (artificial sounds/ natural sounds; silences or rests), and Visual mode (colors; significant things; cinematic elements such as camera movements, perspective, and lighting; gestures and facial expressions; images). The macro analysis phase involves attaching a more abstract meaning, recognizing and reconstructing the perspective and message, as well as identifying and extracting the film’s themes.

Phase 2 (identification of metaphors): six steps (steps two to seven). In this phase, specific metaphors in the film are identified, and the referential description obtained in the previous phase is organized to simplify the film’s components and clarify what occurs in the film in the simplest way possible. Ultimately, if the results of this comparison suggest that something about the film is being expressed indirectly, the unit related to the film can be considered metaphorical, meaning it contains components that can be associated with a metaphor.

By combining cognitive linguistics with multimodal analysis, FILMIP helps to comprehend the way in which a film conveys abstract concepts such as identity, freedom, or power through metaphorical representations across different semiotic channels (Mir, 2019; Forceville, 2009).

- 2. 2. Conceptual Metonymy

Metonymy is a cognitive process in which, according to Radden and Kövecses (1999), a conceptual entity called a “vehicle” provides mental access to another conceptual entity called the “target”. One of the fundamental characteristics of metonymically connected target entities and vehicle entities is that these entities or things are “close” to each other in conceptual space. Metonymy is a specific type of profiling/ backgrounding, which, in cognitive linguistics, is regarded as a conceptual shift in reference (Hart, 2011). This construal tool, based on Shokati Moqarab et al. (1400 [2021 A.D.]) helps to discursively identify in-groups and out-groups.

- 3. 2. Force- Dynamic

Force-dynamic is one of the tools of cognitive semantics, which, according to Talmy (2000, p. 409), contains:

The Agonist and the Antagonist; the Agonist is the focal force entity and the force element that opposes it the Antagonist. An agonist is an entity whose conditions are discussed and is exposed to diverse force interactions from the Antagonist. Agonists tend either to steady-state (rest) or toward action. Based on the perceived strength of the Agonist and the Antagonist, the Antagonist can either realize its intrinsic tendency or not.

As shown in Figure 1, exerting force, resisting it, overcoming resistance, blocking, and removing hindrances are examples of force-dynamic patterns. In force-dynamic, it is the Agonist that receives the focal attention. An Antagonist is an entity positioned against the Agonist, either overcoming its force of an Agonist, or/ and is defeated by it (Talmy, 2000, p. 409). The main elements of the entities are illustrated in figure. 2.

- 3. Methodology

This study will employ a descriptive-analytic methodology. The relevant scenes from the selected film will be meticulously scrutinized to examine their cognitive conceptualizations, utilizing several construal tools, including conceptual metaphor (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980), the multimodal theory of metaphor (Forceville, 2006, 2008, 2016), force-dynamic paradigms (Talmy, 2000), and metonymy-producing relationships (Radden & Kövecses, 1999). These tools compromising the micro-level will be used at the macro-level to discursively analyze the represented discourse, using Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory.

As emphasized in the theoretical framework, this study is composed of three levels: micro (descriptive), meso (interpretive), and macro (explanative), using Fairclough’s (1989) approach. The micro-level contains the construal tools of metaphor, metonymy, and force-dynamic patterns. These tools help identify the role of multimodal selections in the discourses’ articulation. The micro-level describes how words, colors, specific type of music, or camera angles are selected. “‘Texts’ in the first level, stand at the core of the model and are explored through the same forms of linguistic analysis that are used by critical linguistics; to illuminate the way the text represents social reality and the way it portrays the identities and relations of the participants in the textual universe” (Fairclough, 1989, p. 24). In the second, interpretive, level, the relation between these selections and their related context is interpreted. According to Fairclough (1989, p. 24):

The second dimension of analysis deals with ‘discourse practices’ – that is, the processes through which the media text is produced in media institutions and consumed, or ‘decoded,’ by the audiences and users in the context of everyday life. The discourse practices are seen as mediators between texts and macro-level ‘sociocultural practices,’ which constitute the third dimension of analysis. On this level, the phenomena brought to light by the other two dimensions are viewed as the macrosocial processes that characterize the societal ‘order of discourse’ at a given point in time.

The interpretation helps identify the way in which a context-based selection moves towards discourse articulation. There is an intertwined connection between the three levels. Although the study counts three levels, they do not have a clear-cut border, and while talking about a specific metaphor at the micro-level, its meaning-making in its related context is also mentioned in the analyses. The macro-level is studied when talking about the in-groups, the out-groups, discursive Agonism and antagonism, signifiers and sign systems, and the chains of equivalence and difference. Using this three-level method, cognitive construal tools are used at the micro-level, the context-based analysis is done at the meso-level and the discursive, explanatory level is analyzed in the third one. The analysis of the semiotic system, other-makings, and chains of equivalence and difference is also done in the third level.

- Data Analysis

This section aims to integrate cognitive linguistics with discourse analysis to provide a multimodal, cognitive-based discourse analysis of the film. The previously mentioned construal tools will be explained at the micro-level, understood at the meso-level, and applied and elucidated at the macro-level, which pertains to discourse analysis.

4.1. Cognitive-Critical Discourse Analysis

As previously explained, this study conducts a cognitive-based discourse analysis. The initial phase involves identifying the key categories that will form the semiotic system of the research. The semiotic system is developed through cognitively descriptive analyses that are categorized after being examined at the micro-level. This micro-level analysis has led to the identification of several categories at the meso-level. These categories form the foundation for understanding the semiotic system, which will be elaborated on at the macro-level. It is important to note that this is a discursive analysis aimed at examining the antagonistic relations between two discourses: Western discourse and post-revolutionary Iranian discourse. The analysis includes metaphors, metonymies, and force-dynamic patterns, which contribute to strengthening the discursive and semiotic analyses. As a result, cognitive analysis is done to help find the deep structure of the hegemon discourse in Septembers of Shiraz. The subsequent section will present the primary identified semiotic categories, which serve as the foundation for the intended deep structure.

- 1. 1. Rejecting Anti-Semitism

One of the most prominent themes in the selected film is the emphasis on anti-Semitism and Israel in post-revolutionary Iran. This theme serves as a foundational element of the film, guiding the audience’s understanding and interpretation throughout the narrative. The film challenges the Islamic Republic’s approach to defining its other-making borders with Zionism, distinguishing it from the Jewish community. It blurs these boundaries and portrays the entire Jewish community, rather than solely Zionists, as the out-group of the Islamic Republic. For example, some of the reasons leading to Isaac’s imprisonment, are his travels to Israel; Mohsen[3] talking to Isaac: “Our records show that you travel to Israel quite a bit”. Traveling to Israel from post-revolutionary Iran is considered an illegal act, which can serve as a force to stop the focal entity of the film. The film illustrates that the Islamic Republic, as the stronger Antagonist, places a hindrance the entire Jewish community, which is portrayed as the weaker Agonist.

- 1. 2. Islamophobia

According to Ameli and Nabavizadeh Namazi (1397 [2018 A.D.]), Islamophobia has been a component of Western culture for centuries; however, it has become increasingly prevalent in recent decades. This phenomenon does not have a fixed shape or uniform representation; rather, we are confronted with a variety of manifestations referred to as “Islamophobias.” This discourse has consistently shifted from theoretical frameworks to tangible expressions. The selected film starts with a quote from Rūmī[4], “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and right-doing, there is a field. I will meet you there[5]” (Jalāl Al-Dīn Rūmī, 1178 [1800 A.D.]). This quote, at first glance, embodies the LIFE IS JOURNEY metaphor. In this metaphor, the traveler is destined to meet someone in a realm devoid of right and wrong, which serves as the journey’s destination. However, this is a Persian quote; in this translation, ‘right-doing’ is employed to signify Islam. If we consider a continuum, Islam is positioned on one end, opposite wrongdoing, which represents the extreme of a particular trait. Consequently, this film offers an interpretation that is other-making with Islam and redefining it as an extremist religion.

- 1. 3. Iranophobia

Iranophobia refers to the perceptions held by Israelis about Iran, especially in the context of the events surrounding and following the 1979 victory of the Islamic Revolution. Since that pivotal year, Israeli attitudes toward Iran have been shaped and interpreted through the lens of their own societal (dis)order (Ram, 2009).

In the film’s second sequence, Isaac watches a television report (Fig. 4) on the situation in revolutionary Iran. The anchor states “Just eight months since the Shah fled Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini and his Islamic revolutionaries have consolidated power and transformed the country.” Here, through MEMBERS FOR CATEGORY metonymy, ‘revolutionaries’ are said to mean the ‘Islamic Republic’. The members act as agents working to actualize the overarching goal of the Islamic Republic’s macrostructure. The foregrounding of the MEMBERS suggests that all individuals participating in this CATEGORY are an in-group that rejects those out-groups who do not share the revolutionary ideals.

The first metaphor representing the concept of Iranophobia is Iran IS Prison. Isaac and Farnaz are depicted discussing the revolutionaries while being filmed through a barred window (Fig. 3), which creates the impression of confinement. In this sequence, the image of the bars is mapped on Isaac and Farnaz, making them appear trapped in a prison. Isaac expresses concern about the future of Iran in light of the revolution. This anxiety serves as an emotional force, rendering him a weaker Agonist and altering his intrinsic tendency to have peace, and making him contemplate how to revive his previous circumstances. The new situation in Iran acts as a stronger Antagonist (Figure 5), compelling those opposed to the revolution’s ideals to reconsider their intrinsic tendencies. The anchor continues: “Students, socialists, intellectuals, and indeed just about anyone who is not an Islamic fundamentalist are targeted”. Therefore, Islamic fundamentalism serves as a tool for marginalizing others. These others are not only the minorities like the Jews, but also the students, intellectuals, socialists, and whoever is against fundamentalism.

In this narration, Isaac is grouped with the intellectuals, positioned in opposition to the fundamentalists, who serve as the stronger Antagonists. In the same scene, Farnaz asks Isaac to go up, having wine in her hand. Going up makes the GOOD IS UP metaphor; when they go up, leaving the news broadcasting down, means leaving the bad down. Isaac tells Farnaz, “All that needs is a match and … boom”. This utterance conceptualizes THE REVOLUTION IS A BOMB; this stronger Antagonist (the revolution) has made “the country coming apart at the seams”. “Country” metonymically stands for the nation. Thus, the Revolutionary Guards, representing a formidable antagonist, serve as the out-group for the nation. Their strength is causing the weaker Agonist, the nation itself, to fragment. This revolution embodies a stronger Antagonist that is altering the intrinsic tendencies of the non-Islamic fundamentalists, who are the weaker Agonists.

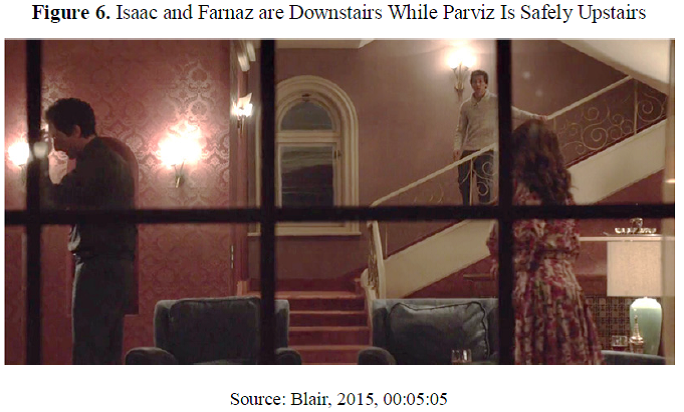

In the same sequence, after Isaac, in a fit of rage, smashes the television, he and his wife are seen downstairs while their son, speaking from upstairs (Fig. 6), asks them, “Mama, Baba! Are you okay?” This scene illustrates the GOOD IS UP and SAFE IS UP metaphors. Their son is sheltered from the harsh realities of society and is ultimately sent to the United States to live. The downstairs setting symbolizes the situation in Iran, representing the BAD IS DOWN metaphor.

In another sequence, a low-angle shot captures the antagonists (the revolutionary guards) as they say to him, “Then come with us”. This angle (Figure 7) symbolizes the weakness of the Agonist (Isaac) and emphasizes the pressure exerted on him by the guards. Uttering words like ‘Yalla[6]’ by them is considered as a physical force exertion.

Different locations depict the revolutionaries’ wielding weapons. The Antagonist employs not only verbal and emotional force, but also exerts physical force to alter the intrinsic tendencies of its out-groups. The hegemony of the Islamic revolution is portrayed as a mechanism for transformation when Mohsen, the interrogator, tells Farnaz, “Now ... It is our turn”. This new phase introduces rules that contradict the will of the Agonists.

One of the main signifiers of the Islamic Revolution is the defense of the oppressed. Upon returning from prison, Habibeh tells Farnaz, “They asked me whether I like being a servant”. The revolutionaries perceive Habibeh as oppressed, and they regard her as a servant. Farnaz then asks Habibeh: “You’re not letting these people put ideas into your head, are you, Habibeh?” ‘These people’ as MEMBERS FOR CATEGORY is used to provide access to the category of the revolutionaries and stereotypically represents those aligned with the Islamic Republic.

- 4. 1. Negative Image of the Oppressed and the Oppressors’ Duality

Habibeh (Figure 8.) re-narrates her son (Morteza): “Why should some people live like kings, and the rest like rats? And why should the wealthy, so crazy for the West and Europe, decide how the whole country should dress, talk, and live? What if we want our mullahs to rule us and not that Saint?”

Morteza, as a representative of the revolutionaries, has shaped and formulated the duality of the ‘oppressed’ and the ‘oppressors’ in his mother’s mind. As shown in figure. 9., Morteza is a MEMBER FOR CATEGORY which gives access to the “revolutionaries,” who themselves belong to a category that represents the Islamic Republic.

So, the oppressors—including the kings, the wealthy, and those enamored with the West and Europe—are rejected by the revolutionaries. Conversely, the in-group, which comprises the rest of the population excluding the wealthy, seeks to support the oppressed. According to the revolutionaries’ ideology, the entire country is oppressed by those who dictate not only the dress but also the manner of speech.

In alignment with this perspective, Habibeh identifies herself as part of the oppressed group when she states, “You put me down every chance you get.” This illustrates the BAD IS DOWN metaphor, where Habibeh, feeling suppressed by Farnaz, her Antagonist, assumes the role of the Agonist within the discourse of the revolutionaries.

Habibeh is metonymically MEMBER FOR CATEGORY, the member is given to access the Islamic Republic as the category. This metonymy signifies that the Islamic Republic has transformed homes into prisons. As a member, Habibeh gradually adopts the thoughts and ideas of the revolutionaries and acts as a guardian toward Farnaz. Farnaz is confined to her own home, which has become a prison. Habibeh exerts her verbal force, telling Farnaz, “This practice [drinking], khanoum, will have to stop.” Although being a servant, Habibeh exerts her force to move that Agonist toward changing the intrinsic tendencies. She continues, “Whether it’s one glass or ten, it makes no difference. It is illegal now.” Here, the term “now” signifies a new order and a new force, as Habibeh exerts her force to completely suppress Farnaz’s tendency. Their home has transformed into a prison; in this context, drinking is prohibited, and Farnaz feels compelled to adhere to the rules. Habibeh makes HOME AS PRISON and enforces the regulations within their household.

As there is no meaning fixation for the signifiers, each discourse assigns different conceptualizations to a single signifier. In the scene where Habibeh pulls the curtains while giving commands to Farnaz, she allows light to enter, which contradicts Farnaz’s wishes. This light is embraced by the revolutionaries and serves as a tool for force exertion.

Farnaz, being at home, which is a prison, tells Habibeh: “Is that a threat?”

This situation represents an emotional force exertion, leaving Farnaz feeling threatened. She is uncomfortable with the new rules imposed upon her by Habibeh. This verbal and emotional force puts Farnaz in a prison-like environment, with Habibeh acting as the guard.

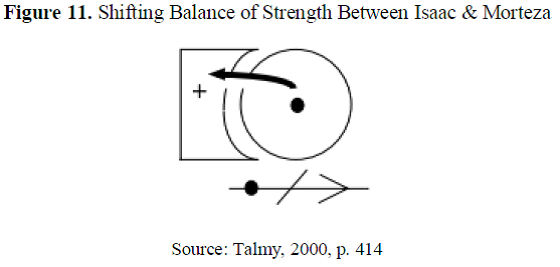

In another sequence, after being released from prison, Isaac returns to his jewelry store, where he coincidentally runs into Morteza, who with a threatening tone, says: “You give me that diamond or this piece of paper[7] will be sent to the office of Imam Khomeini!” as an Antagonist (Figure. 11.), he tries to exert his force on Isaac so that he can gain the diamond. But this Antagonist encounters an Agonist who is also exerting his force on the Antagonist, trying to keep his intrinsic tendency, which is the possession of his only property, the Exquisite precious stones. Isaac replies: “You listen to me, you little shit! You snitch! I am on better terms with the office of Imam Khomeini than you will ever be! After all, I am one of their biggest donors!” In this dialogue, the Agonist and the Antagonist experience a shift in their balance of strength in which “The Antagonist and Agonist can continue in mutual impingement, but the balance of forces can shift through the weakening or strengthening of one of the entities” (Talmy, 2000, p. 419). ‘The office of Imam Khomeini’ is the metonymy of place for the people and generalizes all those in the office as acting the same way.

- 1. 5. Iranian Nationalism

While in prison, Isaac gazes at the cartridge case and states, “we were all equal … Didn’t matter”. The juxtaposition of this statement with a close-up of the cartridge illustrates how this case delineates the identity boundaries among various religions and ideologies. This image represents a CAUSE FOR EFFECT metonymy, in which there is a chain of metonymies; in this chain, CARTRIDGE case is used as a vehicle for the goal FOR force exertion and FORCE EXERTION FOR BORDER-MAKING. Furthermore, as Isaac notes, the Iranian populace once thrived within a just empire in the distant past. Using the past tense verb ‘were’ to indicate equality suggests that such equality is currently absent, underscoring the necessity for its reestablishment within the country. One of the prisoners responds to Isaac, saying, “That’s the problem with this country: we somehow think we’re special because, once upon a time, we were great. Darius, Cyrus, Persepolis ... that was 2,500 years ago. What are we now?” The term ‘country’ serves as a metonymy, representing the people within it. This metonymy generalizes a characteristic to all residents, as Kövecses (2010) notes, “the use of the past tense distances the person from the direct force of the utterance” (Kövecses, 2010, p. 260). In this utterance, Darius and Cyrus are metonymically person for period and Persepolis is place for period. The past serves as a tool for establishing distance. In Isaac’s statement— “because once upon a time we were great. Darius, Cyrus, Persepolis …”—the metaphor GOOD IS THE PAST TIME is evident. When he ironically asks, “What are we now? Barbarians,” he invokes the metaphor BAD IS THE PRESENT TIME. Greatness is portrayed as a phenomenon that belongs to the past, but is conspicuously absent in the present. This absence of culture and civilization is foregrounded by referencing figures and places from history, such as Darius, Cyrus, and Persepolis.

The “GOOD IS THE PAST TIME” is reinforced by contrasting our current state with a more civilized past. In this context, post-revolutionary Iran represents the out-group, while the Iranian Empire embodies the in-group for the prisoners. The border between in-groups and out-groups is underscored when Isaac asserts, “Not all of us are barbarians.” This statement indicates that Isaac delineates the in-groups from the out-groups, categorizing the latter in the “barbarians” category. ‘Us’ refers to the in-groups who share the common characteristic of not being revolutionary.

Both Isaac and Farnaz are in different prisons. Isaac is reminiscing with his cellmates, while Farnaz, in her “home IS prison” is looking at the past, by watching their wedding film and conversing with her cellmate, Shirin. At this point, flashback scenes reinforce the good IS PAST metaphor.

Isaac is interested in Hafiz and copies the text in his own handwriting. Hafiz is the only book he carries with him that embodies the Iranian culture. The sole book of the revolutionaries is the Quran, which signifies Islamic ideology. Consequently, the pre-revolutionary Iranian culture is supplanted by the post-revolutionary Islamic ideology.

- 1. 6. Sacred Suffering

The film opens with Isaac Amin stating, “I guess the last year has been ... challenging. It’s one way to put it. Very challenging for all of us. But, uh ... we’re still here, and we’re celebrating”. In this statement, the metonymic conceptualizations of THE LAST YEAR FOR THE LAST YEAR OCCURRENCES and THE LAST YEAR OCCURRENCES FOR THE REVOLUTION are employed to illustrate the negative effects of the revolution. Conversely, ‘the last year’ serves as an Antagonist, altering the intrinsic tendencies of the Agonists, who are ‘all of us’—those participating in the celebration. In this force-dynamic relation, challenges are metaphorically represented as hindrances: CHALLENGES ARE HINDERANCES. The past year can be understood as a journey filled with obstacles and challenges, encapsulated by the metaphor LIFE IS A JOURNEY. The individuals celebrating are likened to travelers in the same vehicle, confronting similar difficulties. They form a group that has faced challenges from another dominant group referenced in Isaac’s statement. This film narrates events occurring eight months after the Islamic Revolution in Iran, with ‘the last year’ closely associated with this pivotal event.

Emphasizing that “We’re still here, and we’re celebrating” signifies that the in-group, as an Agonist, has overcome obstacles and challenges, emerging victorious and alive in its celebration. This celebration indicates that the Agonist is stronger than the Antagonist (Figure 12); after confronting the Antagonist’s forces, it has managed to recover and regain its previous stability. Such confrontations with the Antagonist suggest that this group has endured hardships to achieve a stronger goal. Talmy (2000, p. 415) articulates this situation as follows: “The Agonist still tends toward rest, but now it is stronger than the force opposing it, so it can manifest its tendency and remain in place. In this case, the Agonist’s stability prevails despite the Antagonist’s force against it.” Isaac and his Jewish family strive to maintain stability, while facing the Antagonist; however, the Agonist’s force surpasses that of the Antagonist, allowing them to continue their intrinsic force, thus affirming their presence.

- 1. 7. Messianic Redemption

Redemption encompasses several specific meanings. According to Biblica Judica (Clark, 2003, pp. 76-77), it “is salvation from the states or circumstances that destroy the value of human existence itself”[8]. One metaphor that embodies redemptive thinking is GOOD IS UP. This metaphor implies that ascending in moral and ideological perspectives is positive, while BAD IS DOWN indicates a negative connotation.

In Peter (1:18 in James, 1982, p. 1067) it is said, “For as much as ye know that ye were not redeemed with corruptible things, as silver and gold, from your vain conversation received by tradition from your fathers”. “Redemption consists of substitutionary blood-shedding with the view of purchasing to Himself many on whose behalf. He gave His life a ransom” Isaac sacrifices himself to achieve redemption, and the blood seen in the picture is the same blood that sets him free. Isaac breaks both the glass of his television and the glass at his wedding with Farnaz in two separate incidents[9]. The shattered screen (Fig. 14) of the television symbolizes the fractured temple (Fig. 15) he experienced in Iran. In the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution, he finds himself in circumstances that compel him to attempt to reconstruct the temple, representing his life before the revolution. This endeavor is viewed as a journey toward redemption from a Jewish perspective.

Talking to Shirin about glass breaking, Farnaz explains her reasoning: “It’s to remind us that... even in times of great joy, there is sadness. That love is fragile. It can break if you’re not careful.” Her statement signifies that the period of immense joy has ended, giving way to sorrow due to the neglect of that joy. The current state of the nation and the transformation of the political system reflect a disregard for this profound happiness. Continuing Isaac’s discourse about the Great Empire with his fellow inmates, Farnaz addresses the concept of great joy and the consequences of its neglect, positioning it as a central theme of the Great Empire. Both individuals emphasize the metaphor of GOOD IS PAST. Flashbacks to a vibrant past, characterized by the absence of barriers and borders, open doors, and flourishing trees, illustrate the presence of joy (LIFE IS LIGHT). However, following the revolution, this joy transformed into sorrow (sad is dark), symbolized by the destruction of the Jewish temple broken by the revolution.

Referring to the Iranian Great Empire[10], Isaac intertextually mentions Cyrus the Great who is unconditionally praised in the Jewish sources. It is likely that, after the Persian conquest of Babylon, Cyrus had commenced his relationship with the Jewish leaders in exile. Isaac mentions Cyrus as the savior of the Jews and their messiah and wishes to revive the past[11]. After being released from the revolutionaries’ prison, Isaac goes to his jewelry and stands by a wall (Fig. 16), which is intertextually associated with the western wall in Jerusalem[12]. Isaac’s journey toward redemption begins with his position against the wall. With his release, his attributes, functioning as tools of force exertion, have enabled him to overcome his antagonists, propelling him toward the restoration of his stability. These attributes transform him into a stronger Agonist, making the Antagonists decrease their force exertion.

- Discussion

The examination of data regarding metaphor, metonymy, and the interaction of forces indicates that this film focuses on the signifiers of the Islamic Revolution in its portrayal of the ‘other’ (other-making). The film dislocates the nodal points of the mega-discourse of the Islamic Revolution to provide an alternative representation of this discourse and cognitively influence the audience’s perspective on the post-revolutionary hegemon discourse. Islamophobia, Iranophobia, the emphasis on the Agonist’s Iranian nationalism, sacred suffering, and messianic redemption are some of the main signifiers foregrounded throughout the film.

The narrative of the Islamic Revolution delineates a distinction between the impoverished and the affluent, the marginalized and the privileged, asserting its allegiance to all those oppressed globally. This process of other-making within the Islamic Revolution is articulated through the perspectives of figures such as Habibeh, Morteza, Mohsen, and others, who emphasize their oppression by Amin’s family. In contrast, the Antagonists of this family exert their rejecting forces. Habibeh and Morteza categorize the entire nation, including the ‘mullahs’ and the impoverished—whom they derogatorily refer to as ‘rats’—as part of their in-group, proclaiming divine support for the faithful. Conversely, they identify their out-groups as the affluent, the West, ‘Europe’, ‘the Saint’, and ‘monarchs’. However, this Hollywood film disrupts this revolutionary boundary-making by portraying the revolutionaries as ‘thieves’ who pilfer the antagonist’s possessions, infringe upon his privacy, and violate the rights of minorities, such as the Jewish community, while stifling freedom of expression for merely “writing an article here and there”. The depiction of revolutionaries is characterized by their use of weapons, exerting physical, emotional, and verbal force, and engaging in illegal and irrational actions, compelling society to adhere to their prescribed dress code and lifestyle.

Throughout the film, Isaac serves as the weaker Agonist, overshadowed by a stronger Antagonist who rejects all the out-groups solely based on their beliefs. The weak Agonist discursively means the suppressed society. This representation stands in stark contrast to the signifier emphasized by the discourse of the Islamic revolution, which advocates for the defense of all oppressed individuals worldwide.

- 1. The Semiotic System

Based on the previously mentioned data, it can be asserted that Septembers of Shiraz is articulating a new semiotic system within the discourse of the Islamic Revolution. This semiotic system, shown in Figure 17, is represented, illustrating that Septembers of Shiraz has a dislocating and antagonistic encounter with the hegemon discourse of the post-revolutionary Iran.

As the articulated system suggests, Iran/Islamophobia serves as the focal point of the other-making discourse in Septembers of Shiraz. Around this nodal point, signifiers like external (non-Jewish) other, internal non-Jewish other, national heritage, the illegality of the revolution, the irrationality of revolutionaries, the emphasis on Jewish national identity, Jewish family solidarity, messianism, redemption, sacred suffering, and the rejection of anti-Semitism and racist superiority revolve.

- 2. Chains of Equivalence and Difference

The semiotic system in Septembers of Shiraz is characterized by chains of equivalence and difference, derived from the film’s context, based on Talmy’s (2000) force-dynamic patterns. These patterns are illustrated through the relations of the Agonist (Isaac Amin and his family) and the Antagonist (the revolutionaries).

As illustrated in Figure 18, the film’s Agonist positions Jewish society within its closest in-group domain, then Israel, students, socialists, intellectuals, non-fundamentalists, and the Jewish supporters (Habibeh and Mohsen, in the final sequence, are articulated within this chain of equivalence.). In Figure 19, the logic of the difference of the represented discourse is drawn.

According to Figure 19, the film’s logic of difference is characterized by irrational, fundamentalist, and revolutionary thinking, which leads to extremist and Antagonist actions. This chain encompasses several general categories, each featuring the film’s antagonists, including Morteza, Mohsen, the prison guards, the revolutionaries, and, more broadly, the leader of the revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini. The logic of difference is embodied by the Antagonists who exert various physical, verbal, and emotional forces to alter the intrinsic tendencies of the Agonist (Isaac Amin and his family), compelling him to sacrifice his possessions and embark on a messianic journey toward his intended redemption.

- 3. Multimodal Analysis

From a multimodal perspective, elements such as light, sound, banners, billboards, and propaganda images in the streets, along with camera angles, colors, costumes, and dresses, have been integrated with text to enhance the other-making conceptualizations of Septembers of Shiraz. Light is conceptualized in a context-dependent manner, representing the metaphors of GOOD IS LIGHT and LIFE IS LIGHT and BAD IS DARK, and its meaning reproduction takes place according to its context; what is considered acceptable light for Habibeh may be deemed unacceptable by Farnaz. In the context of antagonistic conditions, where Iran is depicted as a prison, the environment is enveloped in darkness to denote BAD IS DARK.

LIFE IS COLOR is represented in the dresses showing a dress code in the film. The black chadors (veils) worn by revolutionary women, in contrast to Farnaz’s colorful attire, signify the malevolence of the revolutionaries contrasted with the virtue represented by others.

Another multimodal element in this analysis is the use of sound. The news, the sounds of street demonstrations, and the voices of protestors are conceptualized as TURMOIL IS REVOLUTIONARIES’ VOICE. The film employs a turbulent sound to represent the revolutionaries. This portrayal is conveyed through indistinct and ambiguous sounds, suggesting that the revolutionaries lack clarity in their ideals; there is no definitive or clear-cut understanding of their objectives. Morteza becomes a member of the guards, while concealing his true identity and expressing disparaging views about them. This insincere engagement with the guards, along with his mimicry of their behavior, reinforces the notion that the revolutionaries have yet to establish a coherent understanding of their principles.

The camera angles correspond with the metaphors of STRONG IS UP and WEAK IS DOWN (Figures 13, 20a, 20b, 21a, 21b). This metaphor places the strong in a position of exerting stronger force, while the weak (down) is portrayed as the entity subjected to the force being exerted upon it.

The visuals in the film are designed to illustrate the metaphor IRAN/ HOME IS PRISON. Throughout the narrative, prison bars serve as a recurring motif; the characters are portrayed as being confined behind these bars in various settings, including their homes, workplaces, and vehicles. The camera perspective is positioned behind a window (Figures 3, 6 & 22b), emphasizing that even within the confines of their home, Isaac and Farnaz are ensnared in a prison created by others, which traps them and exerts their other-making forces.

Isaac’s residence features an Iranian carpet, which stands in stark contrast to the surrounding cityscape adorned with ideological imagery, billboards, graffiti, and various elements of propaganda. This environment illustrates how hegemonic discourse has replaced culture with ideology. The act of tearing down cinematic posters further exemplifies this cultural displacement in favor of ideological representation.

- Conclusion

This research aimed to explore how Septembers of Shiraz engaged with the hegemon discourse of post-revolutionary Iran. To decode this interaction, and considering the Islamic Revolution’s emphasis on the rejection of Israel, the film Septembers of Shiraz, which examines the treatment of Jewish individuals during the revolution, was selected for the study.

To examine the film’s discourse, cognitive tools were employed to uncover the substructures of a mega discourse, specifically the discourse surrounding the Islamic Revolution. Consequently, three analytical levels were established, ranging from micro to macro, to facilitate a systematic approach to the analysis. In this process, the construal tools of metaphor, metonymy, and force dynamic were utilized at the micro-level, analyzed contextually at the meso-level, and integrated with discourse analysis to elucidate the underlying discourse expressed from the Western perspective at the macro-level.

The analysis of the micro-level provided a result containing a mega-metaphor IRAN IS CONTAINER, CONTAINER IS PRISON, and IRAN IS PRISON. One of the most frequent metaphors of this study is Iran is prison; the Jews reproduce this metaphor for the post-revolutionary Iran to ideologically denote that the revolution caused restrictions against personal freedom, women, religious minorities, and the intellectuals. Prisoning the writers and intellectuals, the Jews, forcing women to have Islamic costumes, and having restrictions against alcoholic drinks are illustrated in the film to reinforce this metaphor. Isaac and his family hope to escape Iran, they are filmed behind prison bars and try to find a way to get free from the existing situation. They are represented not only as physically trapped, but emotionally turn to be imprisoned (Farnaz in darkness) to show that this prison is both emotional and physical. Showing how the new regime is going to control the people’s beliefs is a hint to demonstrate that the revolutionaries are guards to control all parts of the people’s lives and all of the people are trapped in this ideological prison.

This prison also bans culture, as the guards tear apart the cinema posters and keep the religious writings on the cinema bulletin. Another cultural characteristic of societies is their religious minorities; however, the Islamic Republic is represented as rejecting this cultural variation and seeking Puritan approaches toward society. This metaphor, more generally, targets the discursive subject’s identities. Minorities have to hide their identity and thoughts, or they will face violent behaviors. As a result, they are forced to move out of the country, leave behind their Iranian identity to preserve their religious identity, and again restore their freedom.

The mega metonymy of this study was MEMBERS FOR CATEGORY in representing the revolutionaries and negatively denoting them. Through this metonymy, the embassy diplomats are members foregrounded to access the broader category of American policy and the revolutionaries are the members of a category that is the Islamic republic. Thus, a member is foregrounded to emphasize the entire category.

Furthermore, the mega-force-dynamic of this study (Figure 23) is “Isaac and Farnaz as weaker Agonists and the revolutionaries as stronger Antagonists”. The results illustrate a process of cognitive other-making that portrays a prison-like image of Iran, creating a negative perception of the revolutionaries as illegal and irrational individuals who antagonistically suppress the weaker Agonists.

The micro and meso- levels serve as the foundation for discourse analysis, leading to the semiotic system of the articulated discourse in this Hollywood movie. This discourse focuses on Iran and Islamophobia, highlights the ideals of the Jewish society, and rejects the signifiers of the Islamic Revolution of Iran, such as defending the oppressed and placing the Islamic discourse as the hegemon in Iran.

The signifiers of messianism and redemption are woven into the structured discourse to emphasize that leaving post-revolutionary Iran represents a form of salvation, while discarding the hijab is comparable to breaking free from the shackles of imprisonment. Achieving redemption by crossing Iran’s borders denotes the emergence of a stronger Agonist (figure 4) in the final sequence.

A multimodal analysis was conducted on various elements, including light, sound, images, and visual representations, such as billboards and propaganda-related visuals, to assess their impact on the articulated and opposing discourse present in the Hollywood movie, Septembers of Shiraz. This analysis explores the dual conceptualizations of light within the discourses of the Jews and the revolutionaries, examines how colors influence the good and evil metaphors and investigates the effects of metaphors and camera angles on the Antagonistic force exertions are analyzed in this dimension.

However, this multimodal cognitive discourse analysis resulted in a well-articulated discourse in Septembers of Shiraz, having Judaism in the nodal point, encountering the revolution’s other-making with Israel, and formulating a chain of equivalence with the intellectuals and the civilized, while establishing a logic of difference having the fundamentalist revolutionaries and the irrationals as the main out-groups.

Two suggestions may be proposed for further research: First, the above article focused on a fictional film produced in the U.S.; the same topic could also be explored in other works such as The Operative (Adler, 2019)and Circumstance (Keshavarz, 2011), which are produced by other countries. Secondly, documentaries, alongside fictional or dramatic cinema, are of great interest, and researchers could investigate works such as Zero Days (Gibney, 2016), Our Man in Tehran (Taylor, 2013), and Coup 53 (Amirani, 2019).